Math and Reading Curriculums That Work With Standard Base Grading

Common Cadre Land Standards (CCSS) have been adopted as the reading and math standards of more than 40 states. All just a few states scheduled full implementation of the standards, including assessments, by the end of the 2014-15 school year. Three states (Indiana, Oklahoma, and South Carolina) have rescinded previous adoptions of the Common Cadre, and others accept fabricated small-scale revisions. This section of the Chocolate-brown Heart Study (BCR) will exploit the variation in state implementation of CCSS to expect at the association of the standards with reading and mathematics performance in grades four and eight, the ii grades tested by the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP).

Previous BCRs introduced two models for assessing the effects of CCSS. The models apply different indicators and sources of data to create implementation indexes. The indexes sort states into three groups: nonadopters of CCSS, medium implementers, and stiff implementers. The 2011 index (IMP11) is based on a 2011 survey of state agencies' use of federal Recovery Human activity funds to implement CCSS.1 States were categorized equally "stiff" implementers if they reported joining a CCSS test consortium and spending money on professional evolution and new instructional materials (19 states). The 2013 alphabetize (IMP13) is based on a 2013 survey of state agencies, requesting their timeline for when CCSS would be fully implemented. Usa that planned to achieve "classroom implementation of ELA-CCSS" by the cease of the 2012-2013 school yr were categorized as strong implementers.

The analytical arroyo has both strengths and weaknesses. A strength is modeling data longitudinally, assuasive each state to serve, in a sense, as its own command. Analyses of cantankerous-sectional information, every bit opposed to longitudinal data, are peculiarly vulnerable to producing spurious correlations. A second force, particularly important in interpreting NAEP gains and losses in 2015, is that the indexes were constructed years prior to the release of the 2015 scores. Advocates and critics of CCSS take labored mightily to present the disappointing 2015 NAEP scores in the well-nigh favorable light for their cause. Making up rules for explaining test scores later the scores are known introduces the usual pitfalls of post hoc assay, and to do then while participating in a political debate should raise alarm bells about the indifference of the analysis.

As reported in the 2015 BCR, analyses employing the two indexes indicated that states engaged in strong implementation of CCSS registered a ane to one and half indicate advantage in NAEP gains from 2009-2013 compared to nonadopters of CCSS. Both indexes were synthetic based on the perspectives of state policy authorities, the elites of implementation efforts. They also simply reverberate the earliest stages of CCSS implementation. This year's study goes deeper by examining reports from teachers and principals on changes occurring inside schools. The information come from surveys conducted every bit office of NAEP.

Please note that the post-obit analysis does not investigate whether changes in item practices have caused gains or losses in student accomplishment. The practices examined here are but being used equally markers for indicating the degree to which CCSS recommendations have penetrated schools and classrooms. The 2011 and 2013 implementation indexes are based on information provided by state policymakers as to the breadth and ambitiousness of land implementation plans. The objective at present is to see whether those indexes correspond with reports from practitioners on how CCSS implementation is actually proceeding in schools and classrooms. Scholars of public policy have long known that frontline implementers (sometimes referred to as "street level bureaucrats") tin profoundly shape the end results of pinnacle-down initiatives.2 In the following assay, responses of teachers and principals to NAEP questionnaires are aggregated to the state level to measure each state'southward implementation of CCSS. Before examining the state-level data, let'due south examine national trends.

The question is whether teachers will readily abandon the lesson plans they've spent years honing through trial and error.

But it appears alter is happening; the potency of fiction is waning. Figures 1-i and 1-2 display the percentage of fourth and 8th grade students with teachers saying they emphasize fiction and nonfiction to a "great extent." The relative importance of fiction is clear until 2011, when it begins to slip. In fourth grade, the 25 percent bespeak gap favoring fiction in 2011 declines to 15 percent in 2013 and to eight percentage in 2015. In eighth grade, the 34 percent emphasis favoring fiction declines to 24 percentage in 2013 and to xvi pct in 2015. Teachers in 2015 were less likely to embrace the superiority of fiction in reading instruction than in the past, and the change is evident in both fourth and eighth grades later 2011.

Fourth and Eighth Grade Reading: The Dominance of Fiction Wanes

Fiction has long dominated reading educational activity. The Common Cadre standards in English Language Arts (ELA) urge teachers to strike a greater balance between fiction and nonfiction. CCSS-ELA recommends that informational texts, including texts studied in classes other than English, should control 70 percent of students' reading materials by the end of high school. The recommendation proved to be quite controversial, with an extended debate breaking out in 2012.three Mark Bauerlein and Sandra Stotsky pointed out that inquiry does not back up the superiority of studying nonfiction in improving reading skills. Moreover, every bit an implementation issue, the recommendation runs headlong into deeply entrenched practice. The question is whether teachers volition readily abandon the lesson plans they've spent years honing through trial and error—and give upwardly the texts on which those lessons are focused.

But it appears modify is happening; the authorisation of fiction is waning. Figures 1-1 and 1-2 display the percentage of fourth and 8th class students with teachers saying they emphasize fiction and nonfiction to a "neat extent." The relative importance of fiction is clear until 2011, when information technology begins to slip. In fourth grade, the 25 percentage point gap favoring fiction in 2011 declines to 15 percentage in 2013 and to eight percentage in 2015. In eighth grade, the 34 percentage emphasis favoring fiction declines to 24 per centum in 2013 and to 16 percent in 2015. Teachers in 2015 were less likely to embrace the superiority of fiction in reading instruction than in the by, and the alter is evident in both 4th and eighth grades after 2011.

Fourth Class Math: Less Emphasis on Data Analysis and Geometry

The main NAEP was first administered in 1990 in math and 1992 in reading. About state mathematics frameworks were modeled after the 1989 standards of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM), with the bones structure of math curriculum stable until adoption of the Common Core. Content was organized by five domains (or strands): number and operations; algebra; measurement; geometry; and information assay (which includes statistics and probability). The NCTM standards envisioned these five math domains—even algebra—beingness taught every year from kindergarten through twelfth grade. To this day, NAEP has a like 5-strand structure and awards each strand a different weight.4

Common Core takes a more restricted view of mathematics than the five strand approach. That means fewer topics. David Coleman, leader of the Common Core project, has described CCSS as focusing on whole number arithmetics from kindergarten through fourth course.five Jason Zimba, one of the lead writers of the CCSS math standards states that they "revise the previous 'strand model' of mathematics content in guild to emphasize arithmetic, algebra, and the connections between them."half-dozen

A change occurred in 4 key practices related to curriculum and education.

Teachers appear to be responding to the new focus. Fourth grade teachers do not teach as much data and geometry as they in one case did. Table one-1 reports the percentage of teachers saying that they heavily emphasize geometry and data in the math curriculum. The proportions stayed fairly steady until 2011, when they began to decline. Neither domain received every bit much attention in 2015 equally in 2011 or prior years.

Eighth Grade Math: A Shift in Course Taking

The get-go decade of the 21st century witnessed a dramatic alter in the math courses taken by eighth graders. An "algebra for all in eighth class" move was bolstered by the rising belief that middle school students should take more rigorous math classes. Enrollment in avant-garde courses—mainly Algebra I, but likewise geometry and other forms of algebra—steadily increased. Enrollment in general eighth grade math courses fell. As shown in Table ane-two, general math was the dominant class in 2000, with a 38 percent to-27 pct enrollment reward over avant-garde math. In the following decade, enrollment in advanced classes boomed. Avant-garde math courses held a 47 percent to 25 percent reward in 2011.

But something happened effectually 2011. From 2011 to 2013, the relative growth of advanced courses stopped dead in its tracks. Then, from 2013 to 2015, enrollment in avant-garde math declined from 48 per centum to 43 percent. Enrollment increased from 26 to 32 percent in general math.

Common Core supports this recent tendency past delineating a unmarried eighth grade math class for all students. Options for accelerating mathematically precocious centre school students past compacting iii years into two are discussed in an appendix to CCSS, but the standards themselves lay out a single eighth grade math form that all eighth graders are expected to take. Equally noted in the written report of tracking and Advanced Placement in this study, opponents of tracking have lauded, every bit a step towards equity, placing all eighth graders in the aforementioned math course.

Is Common Core Related to Changes in Practice?

These national trends point that, concurrent with CCSS's implementation, a change occurred in four fundamental practices related to curriculum and pedagogy. By itself that does not constitute convincing testify that CCSS is connected to the trends, but additional prove strengthens the example. Let'southward first with the obvious: CCSS endorses all of these particular changes in practice. Moreover, three of the changes—the shift away from fiction at both quaternary and eighth grades and the move away from avant-garde math classes in 8th grade—have provoked widespread public debate. In those debates, policymakers stated that the changes were compelled by Common Core.

The California State Board of Teaching, for example, rescinded its policy promoting universal eighth grade algebra when it adopted the CCSS math standards.seven On the 2013 NAEP, 73 percent of California eighth graders were enrolled in advanced math courses, a number that plummeted to 45 percentage in 2015. In 2013, only seven percent of students were enrolled in a general eighth course math class. In 2015, the share of students in general math jumped to 32 pct. EdSource, a California publication devoted to education topics, dubbed the trend, "Retreat from Universal eightth Course Algebra."8

Tabular array 1-3ix displays the changes in practice in light of the BCR's 2013 implementation model. To calculate the data, first, state-level changes in the four practices were standardized by conversion to z-scores, with a mean of 0.00 and a standard departure of 1.00. The base year for each menstruum of modify reflects the betoken in time when, as indicated in the charts above, a reversal in the prevailing national trend occurred. For eighth grade math courses, changes occurring from 2013 to 2015 are reported. For the other three practices, 2011 to 2015 is the time period nether scrutiny.

Curriculum and instruction are changing at the ground level of schooling.

Because a z-score of 0.00 represents change in the average country, the signs of the values in the table are important. Positive scores indicate movement in accord with CCSS, and negative scores indicate alter in practise contrary to CCSS recommendations. The z-score of -0.31 in the start column, for example, indicates that fourth class teachers in non-CCSS states were, relative to the boilerplate state, less likely to de-emphasize fiction in favor of nonfiction. They went against Common Cadre. States with medium (0.03) and strong (0.11) implementation of CCSS, on the other hand, were slightly more than likely than the boilerplate country to place a greater emphasis on nonfiction.

The ii math practices clearly differentiate the states. The fourth grade nonadopters (z= -0.76) are reluctant to de-emphasize geometry and data, whereas the potent implementers are more probable to do so (0.32). The eighth grade nonadopters are more likely to continue offering avant-garde math classes (-0.61) while the potent implementers of CCSS are increasingly favoring a single, full general math class (0.33).

Accept annotation of differences amidst the table's rows. Changes in these 4 central practices differentiate the nonadopters from states embracing CCSS, simply they are not every bit successful in drawing a contrast between strong and medium implementers. The 8th grade reading practice (emphasis on fiction vs. nonfiction) is especially weak in this regard, with strong implementers looking more like nonadopters than medium implementers. In a fashion, this makes sense. When the brouhaha over nonfiction erupted in 2012, defenders of the Common Core argued that the recommendation practical to reading materials taught in all heart and loftier school classes—history, science, and fine art—and not simply to those taught by language arts teachers. Perhaps ELA eighth class teachers in strong CCSS states practise not feel the same urgency to apply nonfiction texts as their fourth form counterparts who, after all, typically teach all subjects in a self-contained class. The determination to give nonfiction texts greater prominence in the fourth form curriculum affects the fourth class instructor alone.

Are Changes in NAEP Scores Associated with CCSS Implementation?

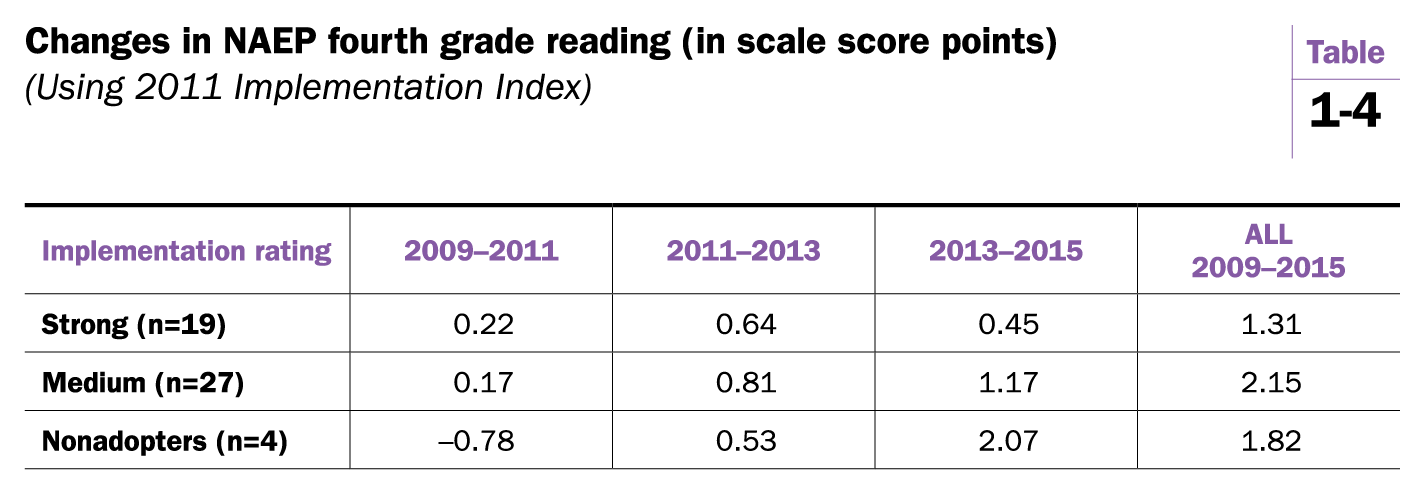

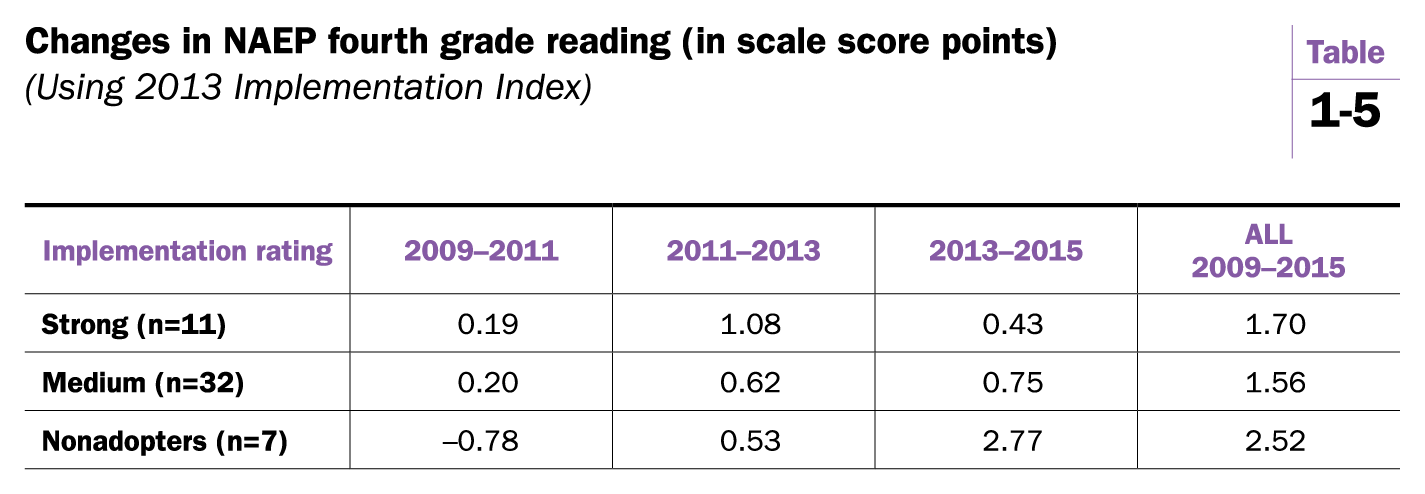

Tables one-4 and 1-5 present changes in NAEP fourth grade reading scores with states categorized by implementation status. Table one-iv sorts us using the IMP11 model and Table 1-5 uses Imp13. The last cavalcade in the tables presents information covering the six twelvemonth period, 2009-2015. Regardless of implementation status, states fabricated only slight progress in reading. The medium implementers made the largest gains (two.15) in IMP11 and the nonadopters made the largest gains in IMP13 (2.52). The gains for all three implementation categories fall within a single NAEP scale score point of each other. The standard divergence (sd) of the 2015 NAEP 4th grade reading scores is 37 points. One indicate is less than 0.03 sd units. That is a miniscule difference, especially if taking six years to emerge. The NAEP 4th grade reading assessment has experienced other half-dozen-yr intervals of underperformance, most notably from 1992 to 1998, when scores were apartment.

Information technology is interesting that CCSS's implementers and nonadopters accept experienced different periods of superior performance. In the early years of CCSS implementation (2009-2011 and 2011-2013), both strong and medium implementers made larger gains than the nonadopters in 4th grade. In 2013-2015, the nonadopters made larger gains, two points or more in the 2013 model. NAEP changes that occur in a single ii-year interval can easily evaporate, and then whether this potential trend continues in 2017 NAEP information volition exist important. The give-and-take below returns to this question.

Regardless of CCSS implementation status, states made just slight progress in reading.

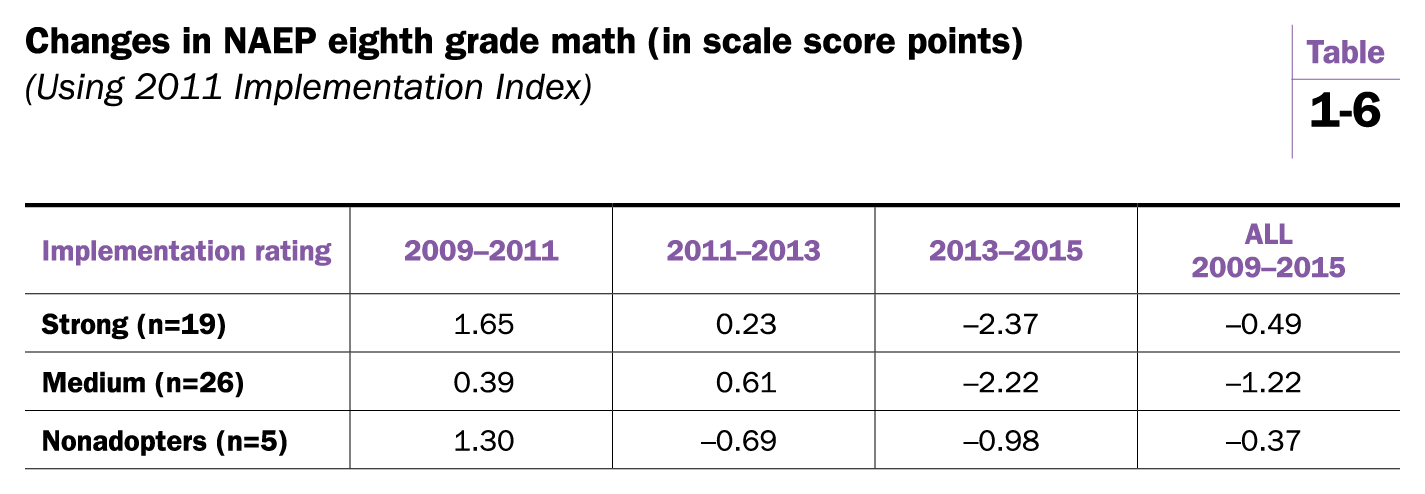

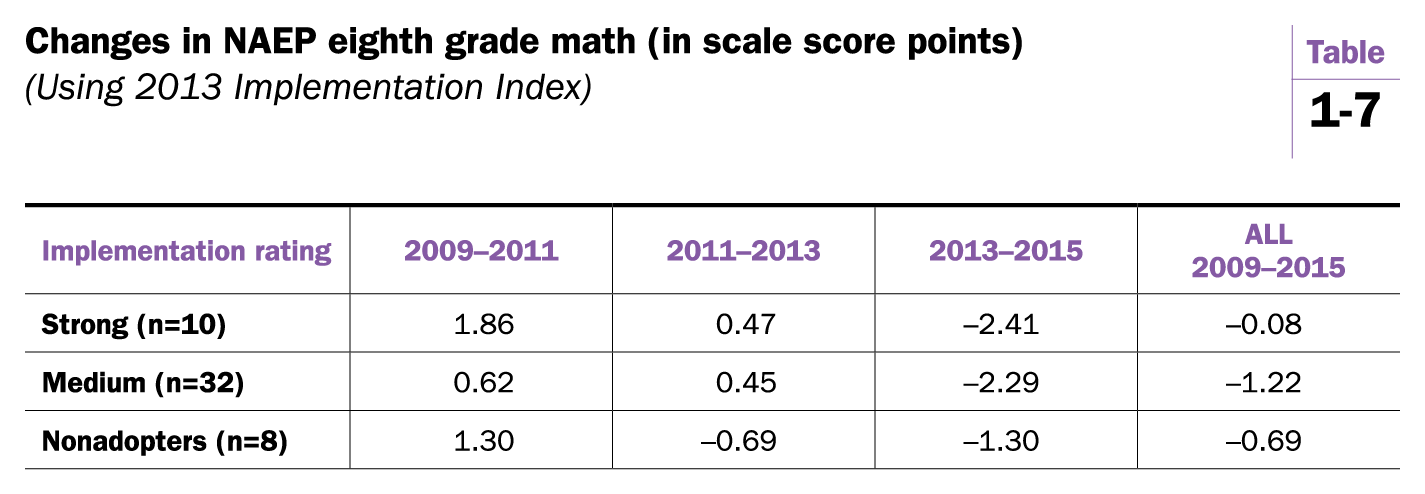

Tables 1-6 and 1-vii examine NAEP scores in eighth class math. Again, the states are grouped past implementation status as defined past the 2011 and 2013 implementation models. The three implementation categories all experienced small declines in NAEP functioning from 2009-2015. To put this event in context, the smallest gain in whatsoever previous six year period on the eighth grade NAEP exam in math has been four points. A loss has never happened before. Nonadopters register the smallest loss in the 2011 model (-0.37) and strong implementers in the 2013 model (-0.08). As in reading, different periods of superiority are evident. Medium or strong implementers notched larger gains from 2011-2013; nonadopters outpaced medium implementers in 2009-2011. The 2013-2015 interval may be a turning point, with nonadopters' scores declining but declining less than the scores of CCSS states. Future NAEP scores will tell the tale.

Whatever is depressing NAEP scores appears to exist more general than the affect of one ready of standards or some other.

Summary and Determination

This section of the Brown Middle Report investigated the Common Core. Recent trends in 4 practices were charted using NAEP data—the education of nonfiction in both 4th and eighth grades, the amount of emphasis given to data and geometry in fourth grade math, and course enrollments in eighth grade math. The CCSS takes a position on all four activities. The information nerveless from teachers and principals on NAEP indicate that these four practices have recently begun trending in the direction recommended by the CCSS: teachers are giving greater emphasis to nonfiction texts at both fourth and 8th grades; data and geometry are receiving less attending in fourth grade math; and at eighth grade, enrollments are falling in advanced math courses and rising in general math courses. Curriculum and educational activity are changing at the ground level of schooling.

States vary on how they await individually on the CCSS reforms. Previous installments of the Brown Center Report introduced models for evaluating the implementation of CCSS. The models sort states into 3 groups: nonadopters of CCSS, medium implementers, and potent implementers. As i would look, the nonadopters appear more than resistant to the CCSS curricular and instructional changes compared to states categorized as having either medium or strong CCSS implementation. The strong implementers were usa almost likely to embrace CCSS reforms, with the exception of placing a greater emphasis on nonfiction texts in eighth course. The medium implementers were the states most accepting of that reform.

The implementation models were used to analyze NAEP scores from 2009-2015. The models show that CCSS implementation is associated with a change of no more than than a single signal (plus or minus) in NAEP for both fourth grade reading and eighth grade math scores. Here'south how that finding was calculated. Dividing the CCSS adopters into ii groups allows for two separate comparisons with the not-adopters. For the eight comparisons produced for 2009-2015, the largest advantage for CCSS adopters is +.61 (Table 1-7, comparing strong implementers with nonadopters on eighth form math scores). The largest advantage for nonadopters is +0.96 (Table 1-5, comparison nonadopters with medium implementers on fourth grade reading scores). A change of one NAEP scale score betoken is lilliputian—and especially and so over 6 years.

This report's analytical approach has weaknesses. It cannot determine causality. States appoint in a lot of policymaking when it comes to education, so declaring that CCSS or whatever other singular policy caused a modify in NAEP scores is unwarranted. Group the states by strength of implementation helps mitigate the result of other polices (assuming that non-CCSS policies are distributed randomly over groups). But the nonadopter group is too small—only iv states in 2011 reading—to have conviction in the assumption. Using changes in NAEP scores over two year intervals helps control for demographic changes—demographic influences should exist baked into baseline scores and not change much over two years—but such influences could bias calculations for the half dozen-year interval of 2009-2015.x The approach is besides statistically unsophisticated. Future evaluations of CCSS will probably take a similar approach, modeling variation amid states (and peradventure districts), then calculating examination score changes over time. Just they also may collect richer information sets and use methods that get across the electric current study's simple comparisons of grouping means.

An intriguing finding from the study pertains to implementation. Adopters and nonadopters of CCSS appear to have experienced unlike periods of superiority on NAEP. The adopters registered larger NAEP gains early in the implementation process, 2009-2013, whereas the nonadopters expect amend in the well-nigh recent interval, 2013-2015 (in the case of math, past registering smaller losses). Many advocates of CCSS accept a theory of implementation that believes these standards are so new, and then revolutionary, and so different from what teachers accept experienced previously that Mutual Core won't bear fruit for many years. Professional development, new textbooks, teaching that targets "deeper learning," and all the other accoutrements of CCSS accept fourth dimension to unfold. Simply wait, good things will happen, proponents say. Michael Kirst, chair of the California State School Board, probably gave the virtually honest statement of this theory by proverb it will take at least some other five years (meaning 2020), a total decade later on California'south 2010 adoption of CCSS, before the state knows if Common Cadre "works."11

The data above support a competing hypothesis. Maybe CCSS has already had its best years and boosted gains volition be difficult to achieve. Major elevation-down reforms tin can have their strongest effects when first adopted, whether it's the NSF-funded science and math curricula of the 1960s, including New Math, or the more recent No Child Left Behind Human activity. Policy elites rally around a new policy, advocates trumpet the benefits that will occur, a public relations campaign is launched to garner support, and local educators reply enthusiastically to the new reforms. New Math started with a bang, but equally criticism grew and teachers' support dissipated, the materials fell out of use.12

The 2015 NAEP scores were a political disaster for Common Core. Eighth grade math scores, for example, fell for the beginning time in NAEP'S 25 year history (down three points). Some observers were quick to point a finger at CCSS. That's probably unfair. The analysis in a higher place indicates that, yes, nonadopters performed better than CCSS states, but only by declining less, non through improved operation. None of the states are setting the world on burn. Whatever is depressing NAEP scores appears to be more than general than the bear on of one set of standards or another.

Part II: Tracking and Advanced Placement »

Source: https://www.brookings.edu/research/reading-and-math-in-the-common-core-era/

0 Response to "Math and Reading Curriculums That Work With Standard Base Grading"

Postar um comentário